1852–1913

Movements

Occupations

José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913) was a Mexican printmaker and engraver who revolutionized popular art and created some of the most iconic images in Mexican culture. Working primarily with publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, he produced over 20,000 images during his career—inexpensive broadsheets sold for a penny on colored paper that made his art accessible to even the poorest workers. He transformed the ancient Mexican calavera (skeleton) tradition, using skeleton imagery year-round for political satire, news reporting, and social commentary rather than reserving it for Day of the Dead celebrations. Despite his enormous productivity and the popularity of his work among common people, Posada never achieved financial success or recognition as a fine artist during his lifetime, dying in poverty and buried in an unmarked pauper's grave. The resurrection of his reputation by Jean Charlot in 1925 established him as a foundational figure in modern Mexican art, profoundly influencing the great Mexican muralists and inspiring generations of social justice artists worldwide.

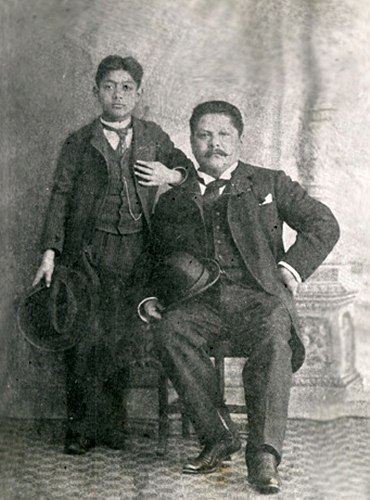

José Guadalupe Posada was born February 2, 1852, in Aguascalientes, Mexico, son of a baker in a family of eight children. His older brother, a country schoolteacher, taught him to read and draw. At fifteen, he was already registered as a 'painter.'

At sixteen, Posada apprenticed with José Trinidad Pedroza, learning lithography and engraving—the technical foundation for his life's work. His first political cartoons appeared in 1871 in the satirical newspaper El Jicote ('The Bumblebee'), which closed after just eleven issues when Posada's caricature offended a powerful local politician. This early collision with authority presaged his career.

Posada spent sixteen formative years (1872-1888) in León, Guanajuato, where he purchased his own printing press at age twenty-four, married María de Jesús Vela, and taught lithography at the local secondary school. He created diverse commercial work: religious images, book illustrations, political cartoons, and advertising art.

On June 18, 1888, a catastrophic flood devastated León, killing over 250 people and damaging his workshop. This disaster, combined with developing contacts in the capital, prompted his relocation to Mexico City at the end of 1888.

The move to Mexico City transformed Posada's art. He learned relief etching on zinc plates—a faster, more economical technique than traditional lithography. He could draw directly on metal plates with acid-resistant ink, then bathe them in acid to leave his designs in relief. The metal plates were nailed to woodblocks and arrayed alongside typeset text, enabling image and verse to print together on single sheets.

This technical innovation allowed remarkable productivity: art historians estimate Posada produced over 20,000 images during his career, working for approximately sixty different periodicals. Around 1889, he began his most important professional relationship: collaborating with publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, who operated Mexico City's leading penny press.

Vanegas Arroyo specialized in inexpensive literature for the masses—corridos (popular ballads), sensational news stories, devotional images, and political satire—all sold through street vendors for a penny. This partnership would last twenty-four years, until Posada's death in 1913. Together, they created a visual language that communicated powerfully to audiences regardless of literacy level (adult literacy in Mexico in 1910 was only 32%).

Despite his enormous productivity and the popularity of his work among common people, Posada never achieved financial success or recognition as a fine artist during his lifetime. He worked as an artisan-craftsman in a modest workshop near the cathedral. Evidence suggests he struggled with alcohol abuse; his death certificate lists 'acute alcoholic enteritis' as the cause when he died on January 20, 1913, at age sixty.

Three neighbors certified his death, though only one knew his full name. He was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave in Dolores Cemetery. Seven years later, his unclaimed remains were exhumed and moved to a common grave. His wife María had died shortly before him, and their only known child had apparently died around 1900. Posada died alone, penniless, and forgotten.

For over a decade after his 1913 death, Posada remained virtually unknown even as his images circulated throughout Mexico. The pivotal moment came in the early 1920s when French-born Mexican artist Jean Charlot encountered Posada's broadsides sold on Mexico City street corners. Charlot didn't know who had created these striking images. He tracked down the Vanegas Arroyo printing house and found the forgotten printing blocks.

In 1925, Charlot published 'Un Precursor del Movimiento de Arte Mexicano: el Grabador Posadas' in Revista de Revistas, bringing Posada to international attention. Charlot described Posada's prints as 'genuinely Mexican' and argued his art was 'connective to Mexico's history and influential to the modern Mexican art movement.'

The timing was perfect. Post-Revolutionary Mexico was experiencing a flourishing of the arts, intellectual growth and education projects, led by Minister of Education José Vasconcelos. The new government sought to define Mexican identity distinct from European traditions. Posada's work represented authentic Mexican popular culture and became central to this nation-building project.

In 1925, American anthropologist Frances Toor began publishing Mexican Folkways magazine with Diego Rivera as art editor, using it to promote Posada through annual Day of the Dead issues. In 1929, Anita Brenner's influential book Idols Behind Altars featured Posada's illustrations, calling him a prophet and linking him to indigenous culture.

The culminating moment came in 1930 with publication of the first comprehensive monograph: Monografía: Las obras de José Guadalupe Posada. Grabador mexicano, produced by Frances Toor's press with collaboration from Blas Vanegas Arroyo and Pablo O'Higgins, featuring an introduction by Diego Rivera. This volume, presenting 406 prints all from the Vanegas Arroyo archive, established Posada's corpus for scholars.

Popular breakthrough came in 1944 with the exhibition 'Posada: Printmaker to the Mexican People' at the Art Institute of Chicago—a collaboration between the museum and the Mexican government. The exhibition was so popular it caused 'mayhem,' with massive crowds overwhelming the museum's capacity. La Catrina graced the cover of the widely distributed catalog, introducing Posada to American audiences.